Closer Racing in F1: 7 Steps to Improve Racing

Closer Racing in F1: 7 Steps to Improve Racing

In 2022, with the principle aim of ‘closer racing’ F1 introduced a major change to its technical regulations; the first major update since 2014 and arguably the biggest technical overhaul the sport has even seen.

Is racing in F1 getting closer following this regulatory introduction? Well, out of the 34 races since the 2022 season began, Red Bull have won 29 (85%) races – all 12 races this year and the last 22 races from a possible 23. Not exactly promising with predictability of outcome the fundamental problem. So, how should closer racing be achieved in F1?

CLOSER RACING IN F1: 7 STEPS TO IMPROVE RACING

First, what prevents closer racing in F1? Whilst many factors contribute to this, the biggest factor is dirty air. When a Formula 1 car (or any object) moves through the air at high speed, it is going to create some form of turbulence. This dirty air significantly reduces the amount of downforce produced by the car following, making it considerably harder to stay close.

To decrease the impact of dirty air, the new 2022 cars would generate the downforce through ground effect instead of relying on the wings, taking inspiration from the 1970s and 1980s. These new regulations, borne from extensive research (over 7,500 simulations), were introduced to allow cars to follow each other more closely.

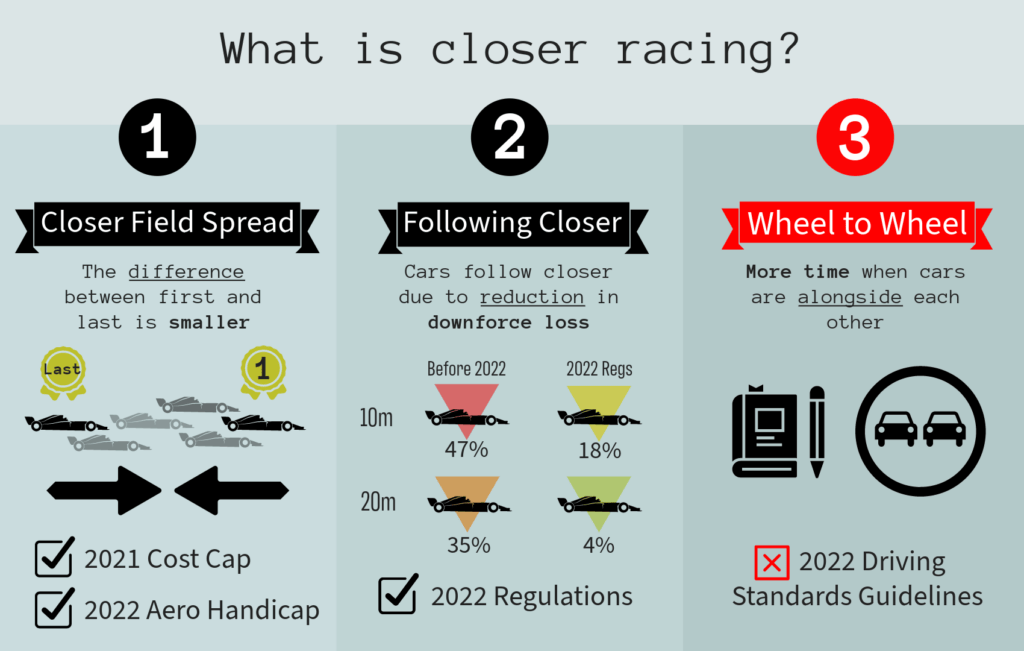

Research from F1 shows that pre-2022 F1 cars lost 35% of their downforce when running three car lengths behind. This increased to a loss of 47% while closing up to one car length. The 2022 car, developed by Formula 1’s in-house Motorsports team, brought down those numbers to 4% at 20 metres, rising to just 18% at 10 metres as illustrated above.

Whilst there were other objectives from the FIA such as sustainability and safety, this article will focus on the closer racing aspect of the FIA’s aim to improve racing through its new regulations. The Seven Steps for Closer Racing in F1 (see below) can be taken in isolation and in any order, though best to work through sequentially.

Step 1: Define Closer Racing

How does the FIA define closer racing?

In terms of racing, the new 2022 regulations were designed for ‘better racing’, more specially ‘to allow closer racing – with the potential for more overtakes a happy, but secondary, benefit’. Firstly, as mentioned above, the new regulations were designed to allow cars to follow more closely by reducing the impact of dirty air. The logic is simple: cars that follow more closely provide more exciting racing, with more drivers / teams with the potential of winning. This seems plausible, the car in 5th position is closer to the car in 1st position, thus has a greater chance of winning. Furthermore, a car following more closely to the car in front has a greater chance of overtaking.

Secondly, the aim of the new regulations was to close up the field by making F1 more competitive. In 2022, the FIA introduced the aerodynamic testing restrictions (ATR) which saw the worst-performing team(s) receiving the most development opportunity. The logic is simple: teams lower down in the Championship will be able to make greater gains in their development to help reduce the field spread.

Thirdly, in its attempts to make F1 more competitive, in 2021, the Cost Cap was introduced. Historically, some teams were spending north of $400m per season, thus the cap simply limited the amount of money each team could spend over a calendar year. The aim was to level the playing field, allowing smaller teams to compete against teams with vast amounts of money. The budget for 2021 was $145m, reduced to $140m for 2022 and $135m for 2023 until 2025. Figures are based on a 21-race season with an extra $1.2m for every extra race and a 3.1 percent raise for 2022due to soaring inflation.

Issues with the FIA’s approach to closer racing

Taken separately, the Cost Cap, the ATR and the new 2022 technical regulations are all a step in the right direction for a more competitive competition, promoting cars to go round the track in closer proximity. However, collectively, these will not increase the likelihood of exciting races. Why? Because it discourages overtaking.

As many F1 fans know, F1 cars need an overtake delta of at least one second on current tracks. Meaning cars with similar lap times, will find it difficult to overtake on a particular circuit (more on overtaking later). In 2023, in Q1 in Bahrain, the top 17 cars were just separated by less than 0.9 seconds. In Australia, the fastest race laps set by the top 16 was only 1.6 seconds. With drivers lacking the adequate delta, this promotes in-race stalemate.

So, closer fields are bad? Absolutely not. To note, when qualifying is so close, a driver error / skill can make a real difference of setting the grid for the Grand Prix. This would help generate a mixed grid – upsetting the natural order – and thus delivering sufficient delta in races. However, this by itself, is insufficient. Undoubtably, overtakes in any motorsport race are a significant appeal to fans and aid ‘better racing’. Arguably, the most exciting (for both driver and fans) is watching a wheel-to-wheel battle for position on the track. Unfortunately, a closer field spread, nor the ability to follow more closely, necessarily promotes wheel-to-wheel racing. And even if it does, wheel-to-wheel action is often seen as ‘boring’ as it involves a car using DRS down a straight.

Remember the FIA’s words “with the potential for more overtakes a happy, but secondary, benefit. The issue here is threefold. First and foremost, the FIA has failed to recognise that cars going round a track in closer proximity does not aid overtaking but actually reduces the likelihood. Second, there are no new regulation / initiatives to actually promote overtaking, thus reducing the likelihood of wheel-to-wheel racing. Third, overtaking should not be a secondary benefit and must be an aim on the same level as making F1 more competitive.

Wheel-to-wheel racing is missing

As illustrated above, closer racing in F1 has three parts to it: closer field spread, following closer and wheel-to-wheel. The FIA have successfully created new regulations for two of the elements of closer racing but failed in finding sufficient ways to promote the likelihood of wheel-to-wheel racing. The 2022 Driving Standards Guidelines are a poor attempt to improve wheel-to-wheel racing (see Step 4).

STEP 1

Define closing racing as having three elements: closer field spread, following more closely and wheel-to-wheel racing. FIA needs to add new initiatives to increase the likelihood of wheel-to-wheel racing, and more importantly, when its achieved, to maintain it for longer.

Step 2: Deal with unintended consequences

A framework to categorise unintended consequences

There is no doubt that a number of the recent regulation changes in F1 are a positive step in its desire to provide better (closer) racing. However, we live in a world of complex systems and “there is a mismatch between the complexity of the systems we have created and our capacity to understand them,” (Sterman, 2006). This is more commonly summarised by the United States Secretary of Defence as known knowns, known unknowns and unknown unknowns.

In the FIA’s quest for closer racing, it is almost certain that there will be unintended consequences. Using the adapted framework from Suckling et al (2021), unintended consequences arising from recent regulation changes are placed in one of four categories: knowable and avoidable, knowable and unavoidable, unknowable and avoidable, and unknowable and unavoidable.

Before looking at the unintended consequences, a number of points need to be noted. First, this is not an exact science, and its purpose is to help future decisions made in F1’s aim of closer racing. Second, context and time matters, thus an unintended consequence can move / change category depending on when this process is taking place. The four unintended consequences have been placed during the 2023 season and not when the new regulations were decided. Lastly, consequences can straddle multiple categories.

Four unintended consequences from F1’s new regulations

The four detrimental unintended consequences are: the aero gain found by teams in 2023; the 2021 Cost Cap preventing teams to close the gap; the infrastructure advantage held by teams; and Cost Cap breaches. Below shows the four unintended consequences placed within the framework.

The first unintended consequence is the aero gain found by teams in 2023 and is categorised as knowable and unavoidable. This undesirable outcome is relatively easy to predict with Haas Team Principle, Guenther Steiner noting its inevitability, “I think we know that from history, you always develop and always when you try to find more downforce, it always damages the people which run behind“. By simple doing their job, aerodynamicists squeeze as much downforce they can get out of any regulations. A recent example of this is the double diffuser in 2009 recouping the proposed performance loss of new regulations.

With history repeating itself once again, this is not just seen in hindsight, but this unintended consequence would have been placed in the same position on the graph when the new regulations were announced. The only way for the FIA to avoid this aero gain was to write technical regulations so tight that did not allow for any variation. If this was the case, then F1 teams may as well pack up and go and allow the FIA to provide 20 or so identical cars. This is simple undesirable and, therefore, the aero gain was simply unavoidable.

Thus, the dirty air problem appears to be showing its inevitable teeth again, making it harder for F1 cars to follow closely. So, whilst the downforce loss in 2023 is less than 2021, it certainly is not the numbers released by the FIA. However, as noting this unintended consequence was knowable, the figures released were best case scenario and needed to be stated as such. In addition, the FIA needs to acknowledge the impact would be countered by teams unless prevented from doing so.

The second unintended consequence is the 2021 Cost Cap preventing teams from closing the gap and is categorised as knowable and unavoidable. This was knowable and as history has shown, when teams start of the season poorly, and when they have the financial might to do so, they tend to develop a B-spec car. However, in 2023, the scale of the car changes Mercedes and Ferrari want to implement are limited on budget grounds.

Toto Wolff, Mercedes motorsport boss, has said, “The cost cap is a real constraint now, because you cannot just go for a B-spec car.” Ferrari’s Fred Vasseur echoes his rivals’ concerns, reporting, “The main driver of this is the cost cap, that you can’t do a new project as was probably the case a couple of years ago.”

Despite this apparent view, the past also shows when there has been no Cost Cap, teams did not exactly reel in their rivals in so easily. Since 1983, there have been nine major rules changes. TheRace analysed (add link reality check for anyone expecting a closer fight) the first eight of these. They found, on average, there is only a small gain between the top two teams, with no significant change in the spread of the top five.

This unintended consequence is placed somewhat between avoidable and unavoidable on the chart for a couple of reasons. Whilst money is a significant factor in helping a team reduce the gap to their rivals, it is not the only option. Teams need to come up with new ways to reduce the gap and the FIA do not know them nor do they know if teams can come up with alternative systems to their rivals to help reduce the gap. Furthermore, working to help teams reduce the gap are the new ART regulations, though as stated earlier, will take time to show its impact.

The third unintended consequence is the infrastructure advantage that teams possess and is again placed as knowable and unavoidable, though is close to unknowable and avoidable. McLaren technical director James Key notes, “It shows that even within a cost cap, if you’re a big team with an extensive infrastructure and a lot of knowledge and methodology built over many years, it still very much counts. It’s a level playing field in terms of the budget we’ve got, but it’s not in terms of where we’re all coming from – that gives us an excellent reference point to aspire to.”

This consequence was somewhat knowable as the FIA know the infrastructure and personnel of teams and know this does impact on performance. Generally, in all sports, great teams neither appear overnight, nor do they disappear. The consequence was more unavoidable than avoidable as teams will use their own facilities, their own personnel and their own systems.

The final unintended consequence is the cost cap breaches, placed as knowable and avoidable. Teams know how much they have to spend and should stop spending when the budget is used. In terms of the FIA, they will know if a team has breached the designated spending allowance.

The Cost Cap has completed its first review with Red Bull found guilty of breaking it. They received a $7 million fine, and a 10% reduction it its ATR. This meant Red Bull had a total 25% cut for 2023 after winning the constructors’ championship in 2022. Team Boss, Christian Horner, stated the punishment was a “significant handicap” to stay ahead of nearest rivals.

In terms of the lead car, closer racing has not happened, from the 29 races since the 2022 season began, Red Bull have won 29 races from 34 (85%). This is further broken down to winning all 12 races this year, and the last 22 races from a possible 23. When the Cost Cap was introduced, then managing director of F1, Ross Brawn, said, “…there are serious consequences if the teams do not respect these rules.” It appears its teeth have yet to leave a mark.

STEP 2

In dealing with unintended consequences, the FIA need to first communicate them, even when presenting the benefits of the new regulations as three were knowable and unavoidable.

Step 3: Introduce DRS Cut-Out

The saviour of overtaking: DRS

As mentioned earlier, a closer field spread and the ability of F1 cars following more closely do not guarantee exciting races. In 2023 Baku Grand Prix, there were a total of 13 overtakes for the entire field. The Canadian Gran Prix had 20 (circuit average in the hybrid era is 31), and Hungary had 16. This is due to the current overtake delta needed in F1.

Trying to increase the number of overtakes in F1 is not new. In 2011, the drag reduction system (DRS) was introduced and works by allowing the following car to open a flap in its rear wing to reduce the drag of the car on a straight, giving it extra speed than the car ahead of it.

Its introduction delivered a near two-fold increase in overtakes the following season. Some overtaking data has shown the average number of overtakes per race since its 2011 to be 44.8. This is compared to 19.9 for the 12 years before DRS. With dirty air affecting all motorsports, especially single-seater cars, the success of DRS in F1 has seen it rolled out into many other racing categories. DRS is a vital aid to overtaking.

The dark side of DRS

Overtakes using DRS is hotly debated. The purist wants it outlawed with the usual criticism brandishing the lack of skill needed, stating it’s too easy. Words such as “artificial”, “gimmick”, and “a band-aid” are often used to describe the DRS. There is no perfect system and there will always be critics. Notwithstanding this, what do other key stakeholders have to say about DRS?

Racefans examined fan ratings of 67 races over a four-year period (2012 to 2015) alongside overtaking data supplied by Mercedes. Over 50, 000 votes were cast where fans rated a race on a scale of one (worst) to ten (best). In its quest to find out how fans rate DRS, wet races were not included, as DRS tends to be disabled.

They found that fans rate races higher when they have more overtaking, but interestingly, DRS overtakes count far less towards the rating than non-DRS passes do. Moreover, lowest-ranked races often had significantly more DRS overtakes than ‘natural’ moves, with very few of the later.

A significant factor that makes DRS overtakes ‘too easy’ is of course the length of the DRS activation zone, i.e., the length of track / straight where it is allowed to be activated. Even at its inception in 2011, Red Bull designer Adrian Newey said, “It will help overtaking…the key is juggling it and adjusting it so that it makes overtaking possible, but not too easy”. In response to these ‘easy’ DRS passes, the FIA shortened some of the DRS activation zones in 2023. One of these was the aforementioned Baku race with a total of 13 overtakes. By using data from the 2022 race, its DRS zone on the main straight was cut by 100 metres.

The difficulty in deciding the length of the DRS zones is summarised by Fernando Alonso, “If you take one car, it was too long, and if you take another, it was too short,”. There are simply to many, ever-changing factors such as tyre length, tyre compound, wind direction and strength. The fundamental issue with DRS appears to be how it is implemented at each circuit, but this is false. The real issue is that the FIA have failed to help DRS achieve its core purpose: to put the driver behind alongside the driver in front. It is time the FIA make DRS what it was intended by employing the DRS Cut-Out System.

DRS needs help to achieve its purpose

So, due to: (1) aerodynamic gains making it harder to follow (again); (2) fans rating races less when DRS passes are significantly more than natural passes; and (3) it being impossible to calculate DRS activation zones for all cars, for all scenarios, for all times, DRS needs modifying. To reiterate, the intention of DRS is to allow the following car to pull up alongside the car in front and then leave it to the two drivers’ skill to either complete the overtake or successfully defend.

DRS Cut-Out System

From the illustration above: steps (1) and (2) are the same as how DRS works currently. The difference for the new system is that DRS is disabled once the attacking [blue] car’s front wing reaches the back of the defending [orange] car (3). Due to the superior speed of the attacking car, it would then pull up alongside the defending car (4). This would look to stop a car breezing past on a straight and promote more closer racing though a wheel-to-wheel battle.

It must be said that the attacking car is likely to get its nose ahead due to the superior speed it gained from the slipstream effect and DRS. Notwithstanding this, the DRS Cut-Out System will significantly increase the likelihood of wheel-to-wheel racing, putting the emphasis more on driver skill. This will also give the defending car more of a fighting chance to either defend its position or to instantly retake it.

It is important to note that the DRS Cut-Out System would likely decrease the number of overtakes overall, however, it would achieve two critical aims. First, it would increase the number of wheel-to-wheel battles throughout a race, adding more excitement. Second, it would increase the number of natural passes, as more battles will lead into and around the corner, again, adding more excitement.

Data from Keberz Engineering shows that the average overtake delta for the 2022 F1 car was 1.174 seconds per lap. This was made up of tyre delta (40%), team delta (36%) and DRS (24%). Since 2017, on average the DRS provides about 20-25% of the overtake delta.

STEP 3

Introduce the DRS Cut-Out System, where the attacking car’s DRS is disabled when its front wing reaches the back of the defending car. Implementation and safety would need to be of course thoroughly studied.

Step 4: Rewrite Overtaking Rules

The FIA’s missing rulebook

By closing the DRS when cars move alongside each other, it will guarantee more wheel-to-wheel racing and the best wheel-to-wheel action: fighting it out around corners. Even better: fighting it out around multiple corners. Whilst a closely fought battle down a straight, into the braking zone is exciting, it does not exactly last that long.

Believe it or not, Formula 1 does not have a rules book for corners, causing several issues. First, F1 has had a Championship every year since 1950 and to fail to give clear rules for racing around corners is an utter failure. Yes, dangerous driving does cover all parts of the track, but F1 needs rules that specifically cover wheel-to-wheel racing around corners other than ‘dangerous driving’.

Second, a typical racetrack length is circa 4.5km. The Silverstone track is 5.891km and using a rough on-the-back-of-an-envelope calculation, is made up of 2.8km of straights and 4km of corners. In other words, the circuit has 68% corners, yet, there are no rules for fighting on this part of the track. This will be different on other tracks, with some tracks having less and others having more. Even if the tracks only have 5% or even 1% of track that contained no rules for wheel-to-wheel action, that is unacceptable. This would be the equivalent of football saying there are no rules in half of the pitch or in the penalty box.

Third, in 2022, the FIA issued new driving standards guidelines to the drivers. This was mainly a reaction from the racing ethics in 2021 which saw a number of highly contentious driving actions, mostly between Max Verstappen and Lewis Hamilton. Not only are these driving standards guidelines seriously overdue, they are only guidelines, and even worse, they are fundamentally flawed.

The two main reasons why the 2022 driving standards guidelines are not fit for purpose are illustrated below. First, overtaking on the inside encourages divebombing and threatens a collision unless the defending driver acquiesces. At point (1), the attacking [orange] car does not have its front tyres alongside the defending car, therefore, according to the standards, the overtaking car does not have any right to space around the corner. At point (2), whilst the defending [blue] car is turning into the corner, the overtaking car still does not have right to space.

At point (3), the attacking car has managed to get its front tyres alongside the defending car no later than the apex. The overtaking car has also managed to do this in a controlled manner (perhaps due to a tyre advantage). So, despite the defending [blue] car not permitted to give space whilst turning into the corner (on the racing line), they all of sudden need to jump out of the way to give space. The FIA’s reference point of ‘no later than the apex’ is too late and drivers need to know if space should be left or not at the lead’s car turn-in.

Second, overtaking on the outside is contradictory. At point (1), the attacking [orange] car is not ahead of the other car, therefore, according to the new standards, the overtaking car does not have any right to space around the corner. At point (2), the attacking car is ahead, therefore, gaining a right to some space.

At point (3), the attacking car is not left space by the defending [blue] car, thus is not given space yet had earned it. However, despite the defending car forcing another car off the track, it has met the new guidelines by making the corner while remaining within the limits of the track. So, at the same time, the defending car has both met the new standards and not.

Let them race philosophy is not fit for purpose

The let them race philosophy morphed into let them sort it out on the track but what it meant was let’s hope they can sort it out on the track evolved into a Wild West free for all favouring a certain style of ‘driving’. In other words, if no one gets hurt, we will just turn a blind eye. Unsurprising, the Race Director has been replaced following the very controversial 2021 season.

It is important to note that the FIA has two main duties to the drivers: safety and fairness. Whilst this article is predominately about the latter, they are inextricable linked as allowing dangerous driving puts a driver at risk and no driver should have to avoid a collision with the other driver deemed to be doing nothing wrong.

To achieve closer racing, two rules need to be added to determine whether a driver is entitled to space around the corner. These rules would promote more racing. Yes, that’s right: more rules would mean more racing. They would allow cars to race side-by-side for longer and, possibly, through multiple corners, instead of a driver being bullied into giving up the fight and the side-by-side action stops. The rules below apply to the attacking car and whether the attacking car has done enough to earn space around the corner.

Rule 1: Had at least ½ a car’s length alongside when lead car starts to break [not on full throttle].

To be clear, lead car means the car that is ahead on track at the time. This could be the attacking or defending car. Now, provided that the attacking car maintains Rule 1 during the braking zone and at the point when the lead car turns in (which could be either car), the [attacking] car is entitled to space around the corner.

Rule 2: Had front wing at least alongside front tyre when lead car turns in.

The purpose of this rule is to factor in the differences in performance in the braking zone, i.e., a second chance to claim space around the corner. This may be due to being on different tyres, fresher tyres or driver/car advantage. See below for illustrations of the rules covering certain / all scenarios.

To note, the defending car must be completely overtaken, i.e., a full car’s length behind, to lose the right to space around the corner. If the defending car has been deemed to be completely overtaken, the rules/roles would then be flipped as the defending car would then become the attacking car (the car behind) and subject to the two new rules. Furthermore, the two new rules apply regardless of the car’s line, i.e., racing line or not. Finally, this article only used video footage aired from the TV broadcasters – more data would have been welcomed.

For reference, see how these ruled played out in the fourteen incidents that saw Verstappen and Hamilton go wheel-to-wheel in the closely fought 2021 Championship.

STEP 4

To have a clear set of rules for drivers around the whole circuit (i.e., corners). These new rules would allow wheel-to-wheel racing to be maintained and not be lost to bullying and/or dangerous driving. Skill and bravery will be on display. Consistency of penalties would also benefit.

Step 5: Modify Track Layouts

Wider cars, less room for overtaking

From 1998 to 2016, F1 cars were 1800mm wide. In 2017, F1 cars increased to 2,000mm (2m), meaning that an extra 400mm of track width is required when two cars go side-by-side. Naturally, the narrowest track has garnered the most attention on the raceability of these wider cars. Over the last few years, when F1 arrives in Monaco, the ‘F1 has outgrown Monaco’ mantra seems to be getting louder. With overtaking in Monaco notoriously difficult, what, if any, impact (in terms of overtaking) has the wider F1 cars had on closer racing?

The graph above produced by AutoSport, shows the number of overtakes in Monaco from 1993 and the width of the F1 car at the time. The article explains the stories behind individual years, such as why 1993 was so high. The reason for placing it in this article is to highlight there’s a very clear decline in overtaking since the regulations changed in 2017.

Now, despite the FIA having stringent criteria to host a F1 Grand Prix such as being at least 12m wide, with the starting grid up to the first corner at least 15m wide, this does not apply to all circuits. Temporary / urban circuits are exempt. For example, the Baku street circuit is only 7.6 meters wide at its narrowest point. The 2023 season will see seven of the 23 races take place at a street venue.

Track tweaks are just tweaks

Over the past few years, there has been notably track changes, with the priorities being safety and more excitement, i.e., more overtaking. In 2021, the Abu Dhabi Grand Prix at the Yas Marina Circuit was reconfigured to specifically allow for closer racing (see below). In 2022, the Australian Grand Prix at Melbourne saw a number of significant changes such as widening new Turn 11 (old Turn 13) approach by 3m as well as cambered to promote wheel-to-wheel action.

Moreover, the Saudi Arabi Grand Prix at Jeddah widened the exit of Turn 27 by 1.5 metres. In 2023, The Spanish Grand Prix will have an altered track layout with the removal of a chicane making for a higher-speed circuit. In trying to make the racing more exciting, race promoters have removed the chicane in the final sector, formerly turns 14 and 15. Ironically the chicane was added in 2007 to promote overtaking.

Whilst these track changes are welcomed, they are neither significant nor enough of them to make a real impact on the racing. Most tracks were built for machinery that didn’t even exist and have failed to evolve with the technology, expectation and today’s rulebook. Melborne widening an approach by 3m is simply not enough – try 6m. And also try carrying it through the corner so the battles can continue. Saudi widening the exit by 1.5m, again, is pretty negligible and will have little impact, if any. Furthermore, any track that needs more than two DRS zones really needs more thought.

More racing lines needed

Drivers simply need more opportunity to show their skill in both attacking and defending, but this is barely afforded by the majority of current tracks. With significant parts of tracks unpassable, overtakes tend to happen in very few predictable places (at best). Deviating from the racing line is just too detrimental. Current World Champion, Max Verstappen says, “The cars are just too wide now. As a result, you cannot drive many other lines, if you are behind someone else.”

Not all tracks need to be super wide (20m plus) at all times. Variation is good. What is needed is multiple places over the course of a lap to overtake, ideally in a natural way too (remember fans enjoy this more). Street circuits certainly have their place in F1 but again, more imagination is needed to offer multiple racing lines around certain parts of the track – at least make it only marginally slower going off the racing line. Whilst approach angle, exit angle, elevation changes, cambering all have an effect, the width of track must be widened significantly in parts.

Of course, cost and space are big obstacles, however, it should not be an excuse, more imagination is all that is needed to reconfigure a track to allow closer racing. With the DRS Cut-Off System and Cornering Rules to enable fair wheel-to-wheel racing, tracks need to foster, not hinder it. Remember, every race is limited by its circuit, F1 is at the forefront of this.

STEP 5

The FIA must support tracks in making significant changes to facilitate more racing lines. This can be done either by widening the track so that deviating from the racing line is not so detrimental or consecutive corners that provide alternative lines (more in Step 7), so DRS is not needed.

Step 6: NEW Team Sprint Race

A wonderful opportunity

Sprint races are shaking up F1 weekend schedule in a big way. The main aim: to present meaningful and progressively engaging sessions across all three days and heighten fan interest throughout a Grand Prix (GP) event. Three sprint races were introduced in 2021, with six sprints in 2022 and 2023 seasons. The sprints have already seen a number of iterations, namely through how the grid is set up, naming and the points system. To help create closer racing in F1, the sprint race needs a further shake up… enter Team Sprint Race (or Sprint Team Race if you prefer).

This would be a standalone event in that it does not determine or influence the starting grid for Sunday’s GP. Normal qualifying would take place on Friday, setting the grid for Sunday’s GP (pole would be awarded for the fastest one-lap time). Saturday’s Team Sprint Race grid would be determined first by the Constructors’ Championship standings. For example, in the illustration below, T1 represents the best performing team, e.g., Red Bull, and T3 represents the third best performing team, e.g., McLaren. The second part of the grid formation would see in effect two reversed grids. T1 would be given grid positions 10th and 20th whereas the team in last position (T10) would be given 1st and 11th.

Over the last couple of seasons there have been six sprint races. Now, the third and final part to forming the grid would be that each driver from each team would have to start half (3) of the Team Sprint Races in the team’s higher grid position and half (3) in the team’s lower grid position. For example, for Mercedes (T2), they would have to choose whether to start Lewis Hamilton or George Russell from 9th with the other one starting from 19th. All teams would then hand in their driver line ups 60 minutes before the race with other teams not knowing what their rivals were doing – a bit like the Ryder Cup in golf.

A fair mixed up grid

Whilst maintaining all the good points such as a focal point for each day, awarding pole and not interfering with Sunday’s GP (it’s a standalone event), it has two major selling points. First, a very mixed-up grid has the potential to add significant value and entertainment along with a strategic element (choice of driver for team grid positions). A differing and more relaxed feel for the day should promote battles between rivals throughout the grid. “So you still have the main focus of the weekend. It is more of a challenge for us and the team, and then we can leave that aside for Sunday when we have the main race, and we have that extra bit of excitement in the middle on Saturday,” says Lando Norris.

Second, it highlights the Team [Constructors’] Championship. At a fiscal standpoint, the Constructors’ Championship is more important to the teams. The teams invest huge amounts on resources, e.g., research and development, and it would be a good thing to promote them a little more with their own race in some way. Also, this format has potential to appease different fans bases such as traditionalists and new, young fans, as well as providing great excitement and closer racing.

There are still several things that would need to be decided but most notable is the points system. Before answering the question how many points should be awarded, a more pertinent question needs addressing: should points count for the individual drivers’ championship? Points would not count towards the drivers’ championship and that points need to be awarded for all positions (except for last), going from 20, 18 17 down to nil.

But what about FP2 practice? There is something else in stall for that, but for now, let’s just digest the amazing new Team Sprint Race.

STEP 6

Turn the Sprint Race into a Team Sprint Race with a split, two-layered reverse grid based on the current Team Championship. With faster cars starting behind, but only immediately behind their rivals, the likelihood of wheel-to-wheel will be increased.

Step 7: Increase Non-Random Variables

In order to create closer racing, the relative performance of cars and drivers need to fluctuate during a Grand Prix. Finding such variables is not easy, especially trying to keep them as ‘natural’ as possible and not appear ‘gimmicky’. The variables need to be subtle, allowing teams to master them by doing a good job and not be the fate of a lottery.

The Joker Lap

A joker lap is an initiative from rallycross where drivers have to drive a designated alternative route once per race. The Joker Lap provides a passing opportunity on a circuit where overtaking is limited. It was first used at Rallycross’s in the 2010 Los Angeles X Games. Below are several track layouts from Rallycross (now called the TitansRX International Series) showing the main track and the joker track. It has featured in every Rallycross championship since its first championship in 2011. The joker lap can either add or decrease time on the lap.

The joker lap has spread throughout the motorsport categories since its inception. It was first introduced in Argentina’s Super TC200 series in 2015, the Suzuki Challenge Series Swift Cup in 2015, the World Touring Car Championship (WTCC) in 2017 and Formula E in 2021. Back in 2020, F1 driver George Russell believes F1 should try the joker lap saying, “Every year we need two joker races or something… Maybe what we need to do – actually this is an idea – on the Bahrain short-circuit is that we do a joker lap on the old circuit. Just one joker lap on the old circuit like rallycross. I think that would be pretty spicy.”

Whilst there is always going to be criticism and aversion to new ideas, the joker lap needs serious consideration in F1. The usual ‘artificial’ gimmick will be thrown at the idea by some, but the joker lap is arguably less gimmicky than DRS, and in essence is just adding another racing line. Perhaps introduce the joker lap into the sprint races, especially as the pit stop variable is (usually) removed.

The joker lap is not too dissimilar to MotoGP’s new idea of the ‘Long Lap Penalty’. So, if a rider has been given a penalty, they will have to take an alternative route which is longer and slower than the normal corner. The long lap penalty has seen it receive positive praise. In the WTCC, the joker lap has also received much positive acclaim from drivers. Honda’s Tiago Monteiro profited from the joker stating that, “Two podiums on a track like this where it’s hard to overtake wouldn’t have been possible without the joker lap,”

Implementation of the joker lap has not always been smooth either such as the 2017 WCTT, but that is not an issue with the concept, but an issue with the implementation of it. Of course, safety is paramount. But safety and space can usually be managed through greater imagination. Just sticking a longer, slower hairpin extending out from the original corner lacks imagination and creates issues on exiting and re-joining the normal racing track. The speed of the cars, track width, where the cars will exit and re-join must all be meticulously studied by the FIA Safety Department.

Other non-random variables

Tyres, Tyres, Tyres. There will always be a tyre conundrum of producing tyres that are consistent and will also wear to produce jeopardy. By producing wear, this increases the number of pitstops, and a race with more than one pitstop increases strategy considerable, and thus produce more exciting races.

Another non-random variable is fake rain. In 2011, then F1 boss, Ecclestone proposed the idea saying, “There’s no reason why sprinklers shouldn’t happen. There’s so much support because wet races are always the best by far.” At the time there was a lot of criticism towards this idea and whilst criticism remains to this day, it is on the wane. The reason wet races are more exciting is because they produce more natural overtakes using more of the track, including more wheel-to-wheel racing around corners. That’s an absolute winner!

STEP 7

To increase the number of non-random variables to races. The new team sprint race would be an ideal opportunity to trail several joker laps, especially as there tends to be no pitstops in a sprint.

Conclusion: Closer Racing in F1

STEP 1: Define closing racing as having three elements: closer field spread, following closely and wheel-to-wheel racing. FIA needs to add new initiatives to increase the likelihood of wheel-to-wheel racing, and more importantly, when its achieved, to maintain it for longer.

STEP 2: In dealing with unintended consequences, the FIA need to first communicate them, even when presenting the benefits of the new regulations as three such consequences were knowable and unavoidable.

STEP 3: Introduce the DRS Cut-Out System, where the attacking car’s DRS is disabled when its front wing reaches the back of the defending car. Implementation and safety would need to be of course thoroughly studied.

STEP 4: To have a clear set of rules for drivers around the whole circuit (i.e., corners). These new rules would allow wheel-to-wheel racing to be maintained and not lost to bullying and/or dangerous driving. Skill and bravery will be on display. Consistency of penalties would also benefit.

STEP 5: The FIA must support tracks in making significant changes to deliver more racing lines. This can be done either by widening the track so that deviating from the racing line is not so detrimental or consecutive corners that provide alternative lines (more in Step 7), so DRS is not needed.

STEP 6: Turn the Sprint Race into a Team Sprint Race with a split, two-layered reverse grid based on the current Team Championship. With faster cars starting behind, but only immediately behind their rivals, the likelihood of wheel-to-wheel will be increased.

STEP 7: To increase the number of non-random variables to races. The new team sprint race would be an ideal opportunity to trail several joker laps, especially as there tends to be no pitstops in a sprint.

The Stat Squabbler says:

- The FIA have most of the tools at their fingertips to promote better racing such as tracks and DRS, they just need to adapt them for the modern era.

- The sprint races are a wonderful opportunity to mix up the grid through the team sprint race as well as trial new non-random variables such as the joker lap.

- Fundamentally, better racing is achieved through more wheel-to-wheel racing.

Do you agree with the Stat Squabble: Should the FIA introduce the Team Sprint Race? DRS Cut-Out System? Which step do you think will help with closer racing the most?

Comment below.